Dr. Donald A. Henderson

On Friday, August 19 Dr. Donald A. Henderson passed away. Henderson was considered a leader in the World Health Organization’s fight to eradicate smallpox. Today, the New York Times published his obituary which we have excerpted here.

Dr. Donald A. Henderson, Who Helped End Smallpox, Dies at 87

by Donald G. McNeil, Jr., The New York Times, August 21, 2016, an excerpt

Starting in 1966, Dr. Henderson, known as D. A., led the World Health Organization’s war on the smallpox virus. He achieved success astonishingly quickly. The last known case was found in a hospital cook in Somalia in 1977.

Standing left to right, Dr. Donald A. Henderson, Dr. J. Donald Millar, Dr. John J. Witte, and Dr. Leo Morris in one of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) former offices. Dr. Donald A. Henderson, headed the international effort during the 1960s to eradicate smallpox. CDC

Like any war, the one against smallpox involved thousands of foot soldiers — notably outbreak tracers and vaccinators — and more than a few generals. They came from both the United States and the Soviet Union, which first called for the disease’s elimination, as well as from other nations.

But, along with Dr. William H. Foege, now an adviser to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Dr. Henderson was considered a field marshal whose combination of vision, bluntness, tenacity and political acumen carried the campaign to victory.

Smallpox, caused by the variola virus, was long one of mankind’s most terrifying scourges. Called the “red plague” or the “speckled monster,” it killed almost a third of its victims, often through pneumonia or brain inflammation. Many others were left blind from corneal ulcerations or severely disfigured by pockmarks.

It is thought to have emerged from a rodent virus more than 10,000 years ago, and signs of it are found in the mummy of Pharaoh Ramses V of Egypt. Some terrified ancient civilizations worshiped it as a deity.

It carried off many European monarchs and buried the lines of succession to thrones from England to China. Because it killed 80 percent of the American Indians who caught it, it was a major factor in the European conquest of the New World.

Three American presidents survived it: George Washington, Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln. In the 20th century, before it was extinguished, it was blamed for at least 300 million deaths.

The victory over smallpox proved the power of vaccine. Before the 18th century, some peoples, especially in Asia Minor and West Africa, inoculated themselves by piercing their skin with pus from victims or inhaling dried pox scabs. Although that sometimes produced a full-blown lethal infection, it killed much less often than epidemics did.

In 1796, Dr. Edward Jenner, an English physician, infected a young boy with cowpox taken from a blister on a milkmaid’s hand. Cowpox, a mild disease, protected those who had it from smallpox, and the modern vaccine era began. The word “vaccine” come from the Latin for “cow.”

Donald Ainslee Henderson was born on Sept. 7, 1928, in Lakewood, Ohio, the son of a Union Carbide engineer and a nurse. He graduated from Oberlin College, got his medical degree from the University of Rochester and did his residency at a hospital in Cooperstown, N.Y.

In 1955, he joined the Epidemic Intelligence Service, the elite disease-detective branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and in 1960, as the chief of viral disease surveillance, he devised a campaign to eliminate smallpox and control measles in Africa. Smallpox had been eliminated in much of the West shortly after World War II, but it persisted in Brazil, Africa and South Asia.

In 1966, he was sent to Geneva to run the World Health Organization’s global campaign.

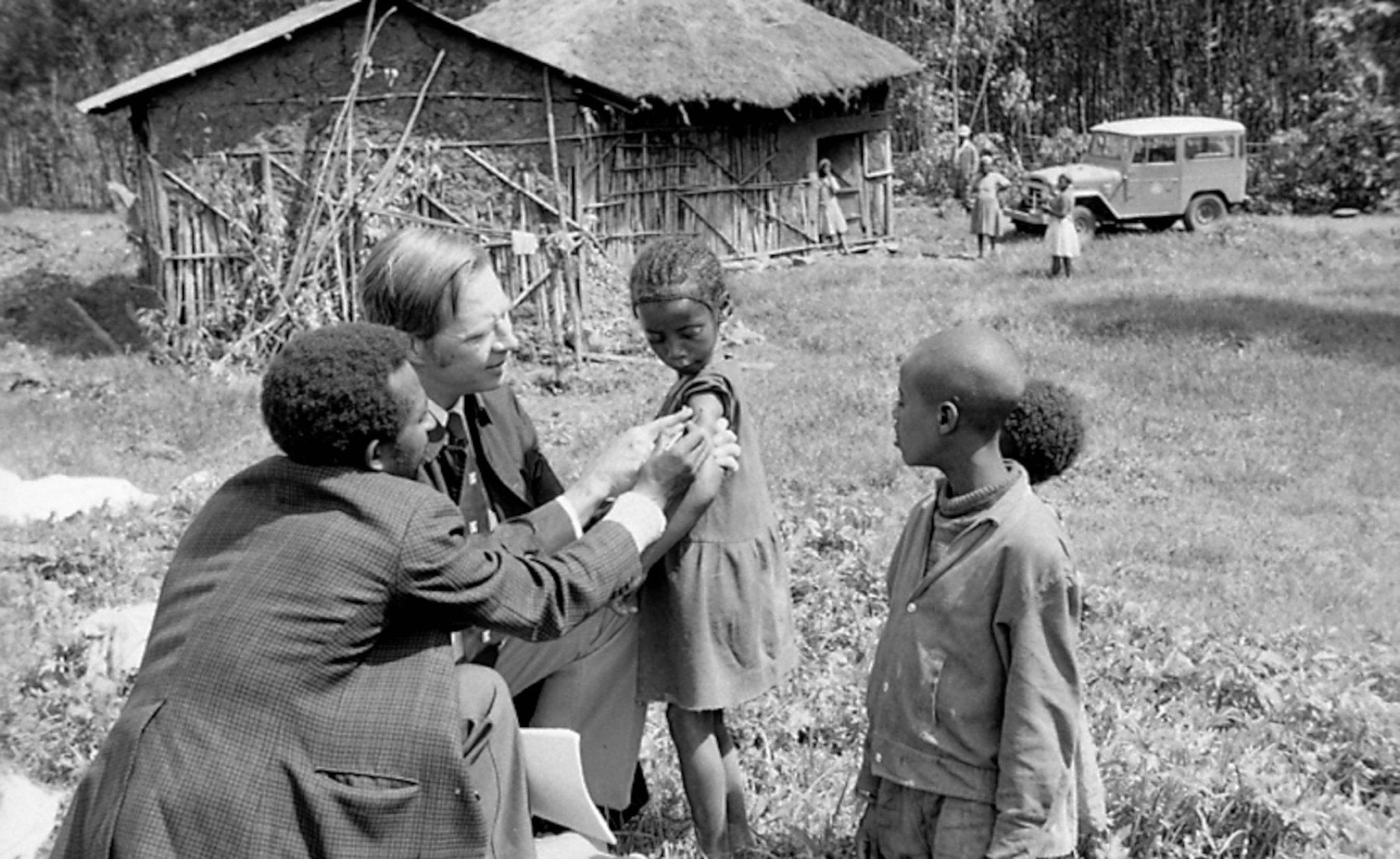

Dr. Henderson working in the field. World Health Organization

“The sense at the W.H.O. was that this was an impossible mission, so they chose a young man who didn’t have a reputation to tarnish,” said Dr. Thomas V. Inglesby, the director of the U.P.M.C. Center for Health Security, where Dr. Henderson was a resident scholar at his death. “I don’t want to say as cannon fodder, but something like that.”

World Health Organization campaigns to end yellow fever and malaria had both petered out, and the organization adopted the smallpox goal only after the Soviets and the Americans insisted, Dr. Foege said. “D. A. always said they wanted an American to blame,” he added.

He was given little staff or support, but remaining on the C.D.C. payroll gave him independence.

“Although outspoken, he understood the absolute importance of diplomacy, and he had the ability to recognize who could go out in the field and get things done with a minimum of supervision,” said Dr. J. Michael Lane, another leader of the fight, now affiliated with Emory University Medical School.

Dr. Henderson spent much of his time visiting smallpox-stricken countries, some of which were also caught up in civil wars. He filed detailed progress reports and threatened to quit when W.H.O. officials asked him to tone them down, Dr. Inglesby said.

When the Soviets shipped weak vaccines, Dr. Foege said, “he went to Moscow and confronted them.”

The campaign developed a freeze-dried vaccine that could withstand tropical heat and be given either with a compressed air “injection gun” or by putting a drop on a forked needle and jabbing it just beneath the skin.

Dr. Henderson's Smallpox: The Death of a Disease was published in 2009, Bill Gates considers it one of his favorite books.

Dr. Henderson quickly realized that trying to vaccinate vast populations was futile and switched to “ring vaccination.” Dr. Foege, who is considered the father of this tactic, said it was “invented by accident” during a 1967 Nigerian outbreak when he had very little vaccine on hand.

“The first night, we asked ourselves what we would do if we were a virus bent on immortality,” he said. They radioed every local missionary asking them to send runners to find out which villages had cases. They sent 80 percent of their vaccine to those villages, using it on the family of each case and all their recent contacts. The last 20 percent went to “anywhere we thought the virus would go next” — which was mostly to market towns where farmers and hunters sold their goods.

“It took D. A. about a year to come around to ring vaccination,” Dr. Lane, who worked with Dr. Foege, said. “But once he did, he was an enthusiastic proselytizer.”

The campaign, many experts have noted, succeeded just in time. A few years later, the virus that causes AIDS spread across Africa. Because the live smallpox vaccine can grow in an immune-compromised person into a huge, rotting, ultimately fatal lesion, it would have been impossible to deploy it.